1 Introduction

$$

$$

Before starting our journey of spatial statistics, we would like to introduce some basic concepts. In the past few years, we found that it is very likely for some beginners in spatial statistics to confuse some groundwork ideas. Making them clear just like the constructing the base of a skyscraper. The following sections are about data, information, theories and applications. We are trying to give readers an explicit and comprehensive view, and make it easier for them to learn models introduced later.

1.1 Relational Data

Before looking in depths of spatial data, we would like to introduce a concept from database theory — “relational data”. It is about how to organize and operate our data. In relational data, data are organized as tables of several rows and columns. Tables are also called “relations”. Rows are also called “records”, “entities”, or “tuples”, while columns also called “attributes”. Thus, data stroed in one table describe things of a same entity type. Note that entities here can be physical or conceptional. Usually, physical entites describe physically esisting substances or objects, while conceptional entities describe relationships between two entity types. For example, the following tables represent physical entities, schools and students.

| ID | Name | Gender | Age | Nation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Student_A | Male | 15 | UK |

| 2 | Student_B | Female | 16 | US |

| 3 | Student_C | Male | 16 | UK |

| ID | Name | Type | City |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | School_A | Primary | London |

| 2 | School_B | Primary | London |

The following table represents a relationship between schools and students.

| Student | School | Join Year | Graduate Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2000 | 2006 |

| 2 | 1 | 2000 | 2006 |

| 3 | 2 | 2000 | 2006 |

For the sake of description, we refer to tables of physical objects as “entities”, while tables of relationships as “relations” in this book. Correspondingly, rows of one entity are called “objects”, while rows of one relation are called “records”. Their columns are both “attributes”.

1.2 Spatial Data

In these days, data are something extraordinary important, existing in almost all parts of our life and work. As the saying goes that “data are carriers of information”, there are variant types of data describing certain kinds of information. There are some examples:

- The growth of gross domestic product (GDP) is used to evaluate the speed of economic development in a certain area;

- Pictures of handwriting words are valuable data sources in training artificial neural networks;

- Articles and posts on the Internet is able to reflect the public opinion on some events and art works;

- Interactions between users and an app are recorded to analysis their preferences;

- Coordinates of trajectory points denoted by GPS would show user’s routine.

Subjects in the statements above are what we called “data”. We can find that data are usually expressed by numbers or something mapped from numbers. The GDP and coordinates (in a certain coordinate reference system) is just a numeric number; pictures and videos are actually matrices of numbers indicating the colour at each pixel and timestamp; articles and posts are essentially series of characters encoded by integer numbers in computer (one of the most popular scheme is called “UTF-8”); and interactions can be represented by events happened in the app, like “at 2 p.m. the user read the post for 2 minutes and pressed the like button”. In summary, data are numbers reflecting certain aspects of information directly or indirectly.

So what is the spatial data? In short, spatial data are “data companied by spatial information”. And spatial information is essentially coordinates or coordinate sets. Sometimes we use the longitude and latitude to represent a pair of coordinates, and sometimes Cartesian coordinate. No matter which form is used, a coordinate and a location on Earth should be corresponded. In other words, coordinates are data reflecting a certain kind of information — locations on Earth. For the sake of description, we refer the coordinates or coordinate sets as the “geometry”. Geometry is the key feature of spatial data different from non-spatial data, as special information can be discovered from these geometries and their relationships.

Usually, spatial data contain not only geometry, but also some other data, like ID, name, area and border length. For example, boundary data of local authority districts in UK also provide each authority’s code; census data provide even more data like the birth rate, index of multiple deprivation and car or van availability. They are the relational data attributes connected to the geometries. Note that no matter for the geometry or the attribute, there needs to be a geographical unit to clarify what entities they are about. For example, if we choose “local authority districts” as the geographical unit when obtaining census data, each item in this data consists of the geometry of one district and the attribute set of it.

A bundle of a geometry and a corresponding attribute set is called a “feature” in spatial data. Thus, a group of features in a spatial data set is actually a entity or relation from the view of relational data theory. The only difference lies in that there is a special attribute representing the geometry.

1.2.1 Type of Spatial Data

As we know, there are varies shapes in geometry, like the point, line, square, rectangle, circle and so on. In spatial data, we can also divide them into different types according to the shape of their geometry.

- Spatial Point Data

-

Geometries in this type of data are points. There is usually only a coordinate to show each feature’s location. Usually this type of data is used to describe positions of events and small scale entities. Restaurants, as an example, can be regarded as points in a city because it is small enough to overlook its area compared with the whole city.

- Spatial Line Data

-

Geometries in this type of data are a connected series of line segments, i.e., a polygonal chain. It is actually a set of coordinates of all vertexes in this chain.

- Spatial Polygon Data

-

Geometries in this type of data are polygons. Actually, polygons are stored as a series of points, which looks like closed polygonal chain. But the difference lies in that a polygon consists of both the polygonal chain (boundary) and area in it. Thus, for polygons we can measure their area, but for spatial line data we cannot.

- Spatial Raster Data

-

Geometries in this type of data are cells of a raster grid. Just like photos taken by digital camera, each feature in a spatial raster data set represents a cell. Position of each cell is captured in this data. Cells in a spatial raster data set have the same width and height.

For spatial point, line and polygon data, each feature can be simple or multiple. And usually there are multiple “bands” in raster data. These bands have the same geographical settings, but capture different data.

1.2.2 Format of Spatial Data

To storage spatial data properly on our computer, there are tens and hundreds of file formats designed in the past decades. In this section, we will only introduce some popular formats, which can be accepted by most geographical information systems.

1.2.2.1 Comma Separated Values (CSV)

This format is probably the most popular one. In a CSV file which is actually a table, each row represents a entity/record. Columns are separated by commas, representing attributes. Geometry information is stored in a special column. For spatial point data which we only need coordinates of those points, there are some columns telling us values of every dimension, such as “longitude” and “latitude”. For spatial line data or polygon data, everything is not that simple. Geometries are represented by texts of a special form listed in a column. From the special texts, we can know what they look like. This form is called “well-known text”.

When we talk about the formats of spatial data, we need to emphasis its difference from file extension name on computer. Data format means how data are organized. But the extension name of a file is just a mark to tell users and the operating system what format data are organized as in this file. For example, the CSV format requires data to be orgranized as a table, and columns to be separated by commas. And files of CSV-format data usually have the extension name .csv. When users found a file whose name has such a suffix, they may realize that this is a file of CSV-format data instantly. And the operating system is able to choose appropriate software to open this file. However, it does not mean that all files of suffix .csv to their names are comma-separated values. They could be a Excel work sheet but with wrong extension names. And also a file of CSV-format data does not need to have the .csv extension name. It still works even there is no extension name, or extension names like .cs, .sv. Above all, there are no restrict relations between file formats and extension names. Thus, converting a file to another format is not as easy as changing its extension name.

The strengths of this data type are obvious. It is readable for human. However, to make it readable, files need a large size of disk space because values need to be converted to texts. For decimal values, they need to be rounded. Such a practice both reduces the precision and expand the file size. For a double-precision decimal number, it needs 8 bytes as a binary value which is as precise as \(\frac{1}{2^{52}}\), but needs 16 bytes to display only 15 decimals. For spatial data, this weakness is critical, because geometries need many decimal numbers to be stored. And when text values contains special characters (i.e., comma and newline), it is confusing for both software and readers. Thus, although CSV is human-friendly, it is not the best choice for spatial data.

1.2.2.2 ESRI Shapefile

Usually it also referred as “Shapefile” or “shape”. This is another famous and popular format for spatial data. Supporting it is almost a standard part of GIS software. Unlike other formats, ESRI Shapefile is actually a format of a group of files. In each group, there is only one type of spatial features. The group includes files of extension names .shp, .shx, and .dbf at least. The geometry is stored in the .shx file of a binary format, while attributes are stored in the .dbf file which is a “dBase” database file. Usually, there is a file of extension name .prj to store the coordinate reference system. Thus, when we refer ESRI Shapefile data, we mean not only the .shp file, but the file group.

Just like CSV data, the strength of ESRI Shapefile mainly lies in its prevalence. As it is acceptable for most GIS software, distributing your data in this format is a good idea on most occassions. However, there are also some problems that cannot be overlooked. First, the loose file organization many cause problems during transfer. So usually we need to put them into a compressed file. Second, names of attributes cannot be longer than 10 characters. This limitation is caused by the “dBase” database. These two limitations affect the user’s experience most. Apart from that, there are many other limitations.1 So I would not suggest readers to use this file format too much. There are many other alternatives.

1.2.2.3 GeoJSON

When you are working with Web GIS, you may be familiar with JSON and GeoJSON. JSON is short for “JavaScript object notation”. And GeoJSON is a special JSON format for spatial data. This is also a readable format. Everything of a feature set is stored in a file of JSON format. As JSON is well supported by Web techniques, GeoJSON can be easily supported by Web GIS. However, as it is readable, it may take up more disk space. There are more special characters in the JSON format, but it is well defined to avoid conflict with text fields. Generally speaking, it is a good choice for spatial data. But it is not widely supported. Be careful when you choose it.

1.2.2.4 GeoPackage

This is a comprehensive format for spatial data. Like ESRI Shapefile, it use SQLite, a file-based database, to store attributes. However, unlike dBase databse, SQLite is extensible and does not limit the length of attribute names. Thanks to the database scheme, there are restrictions to avoid invalid field values. However, as it is a recently released format, it is not supported by as many software as ESRI Shapefile.

We cannot list all existing formats of spatial data here. Readers can turn to https://gdal.org/drivers/vector/index.html to find out more formats.

1.3 Spatial Effects

In 1970, Tobler wrote that “everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things”, which is known as the first law of geography (Tobler 1970). Based on this theory, two types of spatial effects are recognized by most geographers: spatial autocorrelation and spatial heterogeneity.

1.3.1 Spatial Autocorrelation

Before talking about spatial autocorrelation, I’d like to introduce autocorrelation. When we are analyzing the distribution of a group of \(n\) observations \(y_1,y_2,\cdots,y_n\), everything would be easier when they are independent and identically distributed (short for i.i.d.), drawn from a population. We would not want to find correlations between observations themselves. However, for some types of data, such a kind of correlation is likely to exist, such as time series data. Samples generated at time \(t\) and \(t+1\) are likely to be correlated. It may cause estimates of linear model to be biased. This is autocorrelation and why we should avoid it. In spatial data, autocorrelation could be found in nearby samples, because of the Tobler’s law. In this case, when modelling this data, ordinary linear regression is no longer approiate. We need some special techniques.

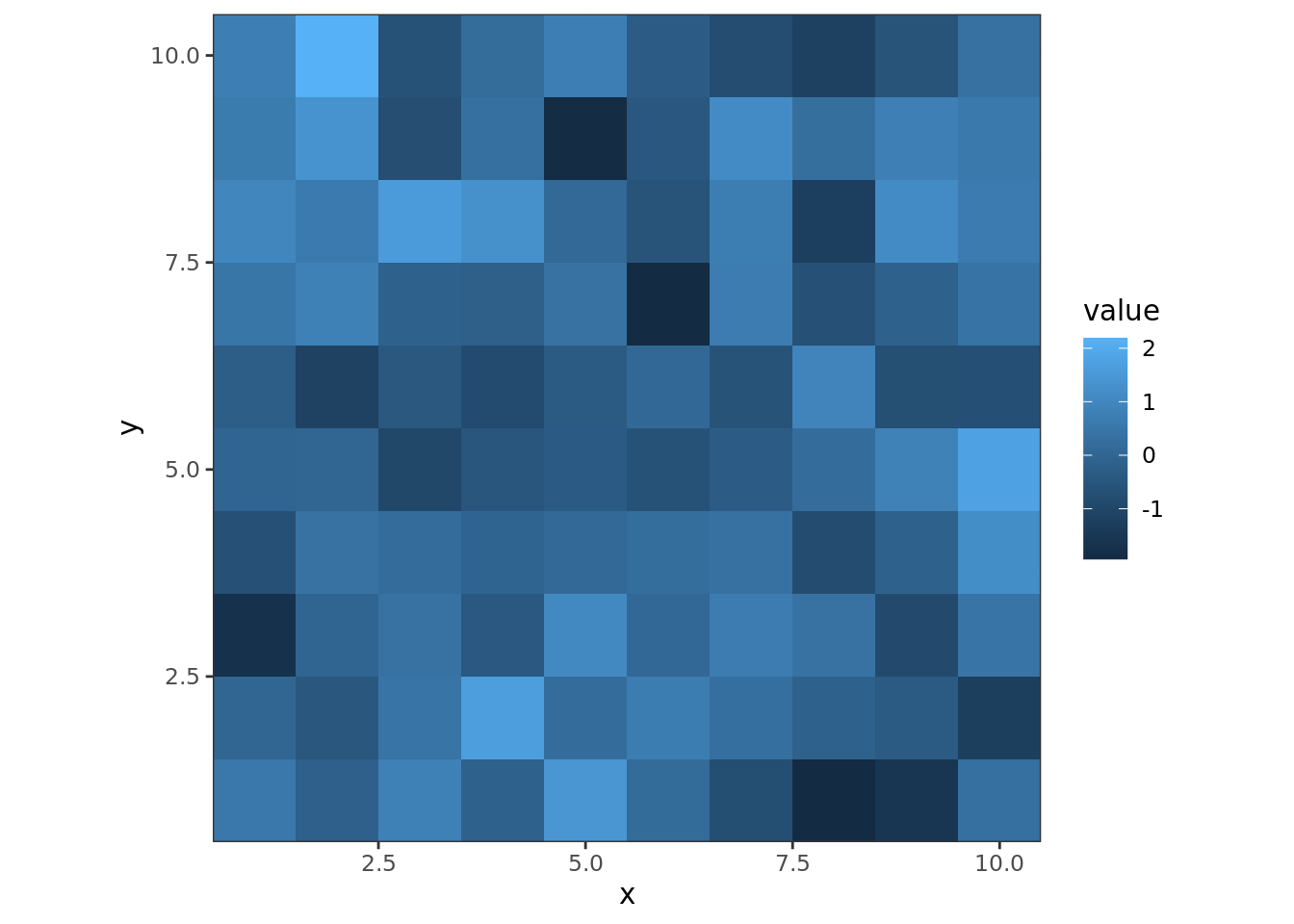

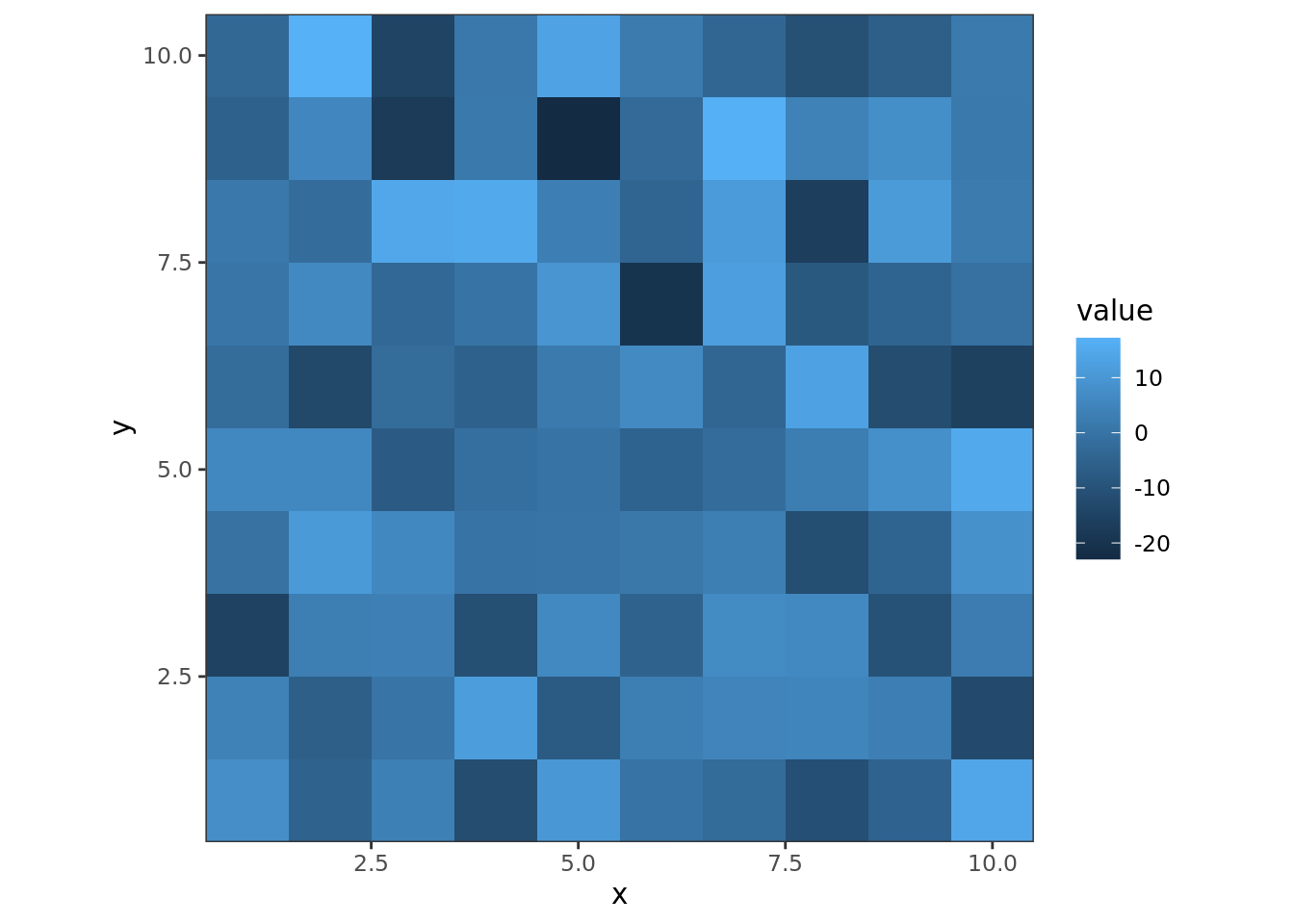

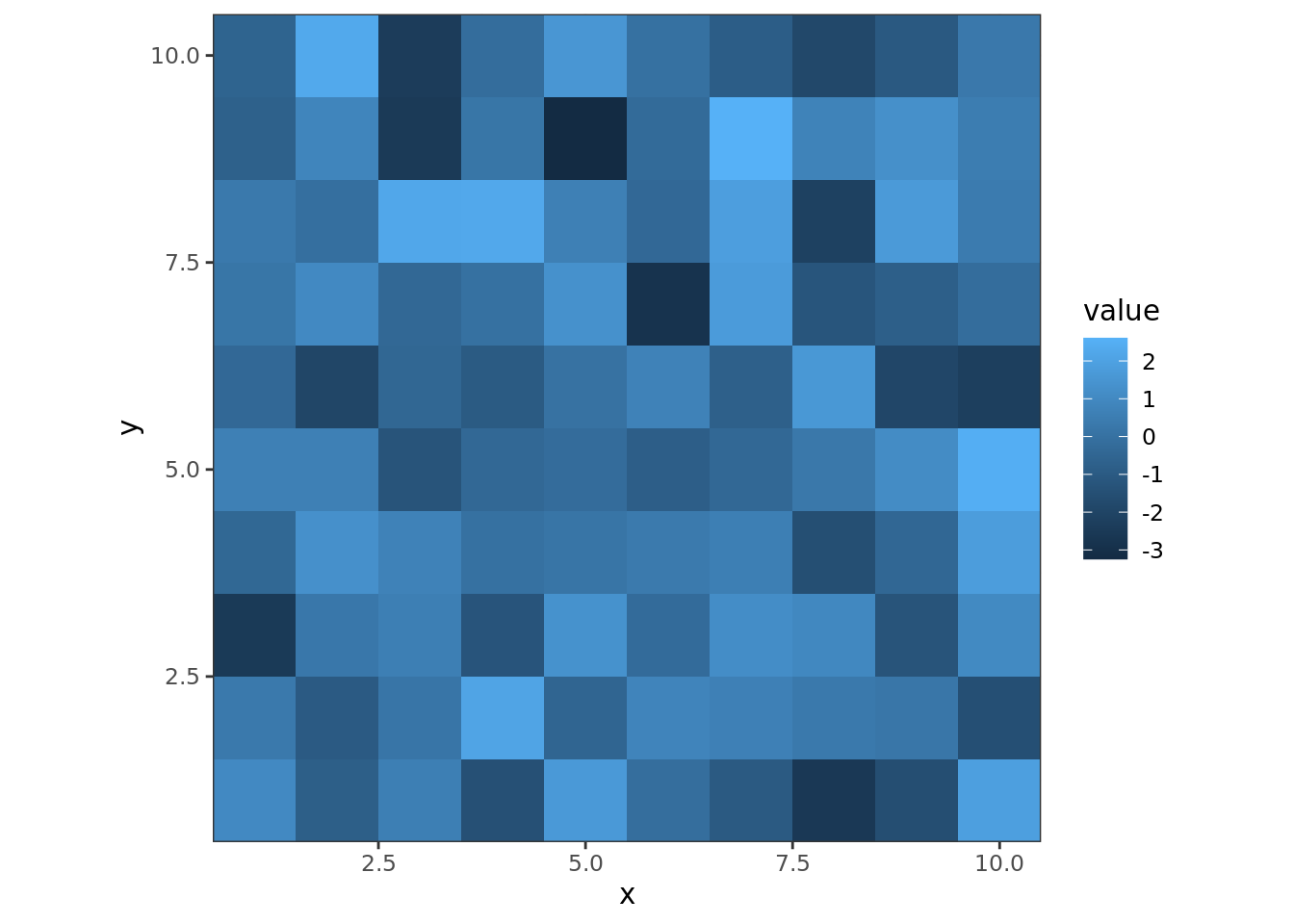

Such an effect is common in our daily life.

1.4 Spatial Statistic Models

1.5 Statistical Software: R

For more information, please turn to this page http://switchfromshapefile.org/.↩︎